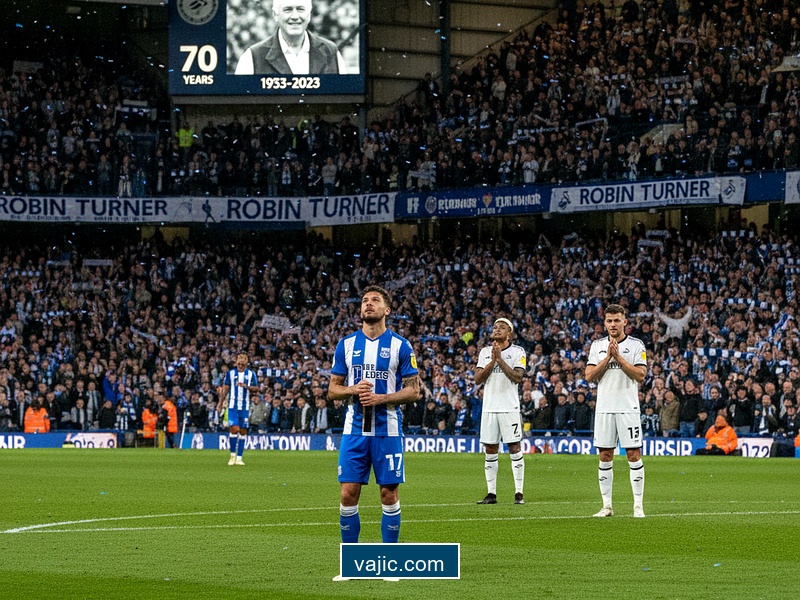

The news from Carlisle to County Mayo this week carries a specific, heavy weight for those who remember football before it was sanitized for high-definition television. Robin Turner has died at the age of 70. To the casual observer scanning the scrolling ticker on a sports news channel, the name might not trigger the immediate reverence reserved for a Pele or a Maradona. But make no mistake: for two distinct tribes—the tractor boys of Ipswich and the jacks of Swansea—Turner was the embodiment of a glorious, grit-toothed era that the modern Premier League has entirely failed to replicate.

We are losing the architects of football's greatest fairy tales. Turner’s passing isn't just the loss of a former striker; it is the dimming of a light on the specific, visceral brilliance of early 1980s British football. He was the ultimate "system player" before the term existed, a forward who operated in the shadows of superstars yet delivered the dagger when the floodlights were brightest.

The Night the Earth Shook in Suffolk

To understand Turner, you must understand March 1981. This is the "Information Gain" that modern box-score analysis misses. Ipswich Town were facing Saint-Etienne in the UEFA Cup quarter-finals. This wasn't just a French club; this was the French club, led by Michel Platini, Johnny Rep, and Patrick Battiston. It was a galaxy of stars descending on Portman Road.

Ipswich had Paul Mariner, the rock star center-forward, and John Wark, the goal-scoring phenomenon from midfield. But on that night, with the aggregate tied and tension suffocating the terraces, it wasn't the superstars who broke the French resistance. It was Robin Turner. His header to make it 3-1 (in a match that ended 4-1) didn't just win a game; it validated the managerial genius of Bobby Robson.

If we look back 20 years to the mid-2000s, we saw the rise of the "Super Sub"—epitomized by Ole Gunnar Solskjær at Manchester United. Solskjær was the assassin with a baby face, a luxury player in a squad worth hundreds of millions. Turner was the prototype for this, but forged in a much harsher metallurgic environment. He wasn't a luxury; he was a necessity. In 1981, squads were thin. Rotation was a myth. Turner didn't come off the bench to face tired legs; he started matches and fought trench warfare against some of Europe's most cynical defenders. Comparing Turner’s role in 1981 to Solskjær’s in 1999 or 2005 highlights a shift in footballing economics: Turner was a working-class hero earning a working-class wage, delivering European glory through sheer aerial dominance and positional intelligence.

The Swansea City Revolution

It is a rarity in sport to be present at the absolute zenith of two different clubs. Most players are lucky to ride one wave; Turner surfed two of the biggest swells in Football League history. After conquering Europe with Ipswich, he moved to Swansea City in 1985, just as the embers of John Toshack’s miraculous revolution were still glowing.

Toshack took Swansea from the Fourth Division to the top of the First Division in four years—a feat that statistically dwarfs Leicester City's 2016 title run when adjusted for financial disparity and timeframe. Turner arrived as the club was grappling with gravity, but his contribution was immense. He wasn't the flash of a Leighton James or the charisma of an Alan Curtis. Turner was the ballast.

In the mid-2000s, we marveled at players like Emile Heskey or Kevin Davies—strikers whose value was measured not in Golden Boots but in bruises inflicted on center-backs to create space for others. Turner was the forefather of this selfless physicality. At the Vetch Field, a ground that retained a menacing, cage-like atmosphere until its demolition, Turner’s ability to hold up play allowed the flair players to operate. He played the "Target Man" role before it became a tactical pejorative. He absorbed the hits so others could take the glory.

The Lost Art of the "Utility" Forward

Analyzing Turner’s skillset reveals a player who would be baffled by the rigid positional play of 2024. Today, strikers are categorized strictly: the False 9, the Pressing Forward, the Poacher. Turner was simply a footballer. He could lead the line, drop deep, or drift wide. He scored 18 goals in 89 league appearances for Ipswich—not a Haaland-esque ratio, but every goal seemed to carry the weight of a cup final.

Consider the trajectory of a player like Divock Origi at Liverpool during the Klopp era. Like Turner, Origi was never the first name on the team sheet, yet he is responsible for the club's most euphoric moments in the Champions League. The difference lies in the ecosystem. Origi was part of a machine optimized by sports science and data analytics. Turner was operating on instinct and the instructions of Bobby Robson, a manager who managed people, not spreadsheets. Turner’s success was derived from a rugged adaptability that is being coached out of the modern academy player.

"Robin was a player you could hang your hat on. He never hid. In games where the mud was ankle deep and the opposition were kicking lumps out of us, Robin was the first one standing tall." — Archived fan sentiment from the North Stand, Portman Road.

Retirement to the West: A Quiet Dignity

Perhaps the most telling aspect of Turner’s life was his post-football trajectory. In an era where ex-pros scramble for media relevance, launching podcasts or shilling betting sites, Turner retreated to the quiet majesty of Erris in County Mayo, Ireland. He integrated into the community, not as a former UEFA Cup winner demanding a table at the restaurant, but as a local.

This mirrors the exit of legends like Roger Hunt or the late Jack Charlton (who also found solace in Ireland). There is a stark contrast between this dignity and the frantic brand-building of the 2020s retiree. Turner’s move to Mayo wasn't a PR stunt; it was a life choice. He became part of the fabric of the connacht soccer scene, lending his expertise to local sides without fanfare. It speaks to a man who played football because it was his trade, not his identity.

The Verdict

Robin Turner’s death at 70 forces us to confront the transience of football glory. The clips of his goal against St Etienne are grainy now. The Vetch Field is a housing estate. The Portman Road of 1981 is a ghost story told to young fans who only know Championship struggles or recent promotions.

But players like Turner are the glue of history. Without the Robin Turners—the reliable, tough, technically sound deputies—the Paul Mariners and John Toshacks do not exist. He represents a bridge between the muddy, brutal reality of 70s football and the tactical enlightenment of the 80s. He was a Carlisle boy who conquered France and settled in Ireland, leaving a trail of integrity in his wake.

In the current market, a homegrown striker with European pedigree and the versatility to play anywhere across the front three would command a transfer fee in excess of £40 million. Robin Turner gave Ipswich and Swansea something far more valuable than a balance sheet asset: he gave them reliability when the pressure was unbearable. That is a currency that has no inflation.