There is a specific silence that falls over a film room when you watch a quarterback who has transcended the "athlete" label and entered the realm of the "practitioner." Watching the All-22 tape of Joe Burrow’s dismantling of the Miami Dolphins isn't just watching a 45-21 box score manifest; it is a clinic in kinetic efficiency and pre-snap neural warfare. While the headlines scream about records and elite status, the real story lies in the biomechanics of the pocket and the invisible chess match played before the center even grips the ball.

The Biomechanics of "Quiet Feet"

In two decades of evaluating quarterback play, the most consistent delineator between "good" and "transcendent" is not arm strength—it is lower-body silence. Most young quarterbacks, when faced with the pressure packages Miami dialed up, exhibit "happy feet." Their base widens nervously, their heels click, and their eye level drops to the pass rush. Burrow operates with an eerie, rhythmic stillness.

Against the Dolphins, Burrow displayed what we call "hitch integrity." Watch his drop-back. It isn’t a drift; it’s a calculated climb. When the pocket collapsed—as it inevitably does in the NFL—Burrow didn’t bail horizontally. He utilized distinct, small hitch steps to navigate the noise, keeping his cleats in the ground to maintain torque availability. This is the difference between a scramble drill and a pocket manipulation. By refusing to break the pocket prematurely, he forces defensive ends to re-trace their arc, buying the offensive line fractions of a second that do not exist on the stopwatch but are eternal on the field.

This is reminiscent of late-career Tom Brady or Peyton Manning circa 2013. It is the understanding that the pocket is not a cage, but a workspace that can be expanded through subtle movement. Burrow’s ability to dissociate his upper body from his lower body allows him to throw off-platform without sacrificing velocity, a trait usually reserved for guys like Rodgers or Mahomes, yet Burrow executes it with the mechanical repeatability of a jugs machine.

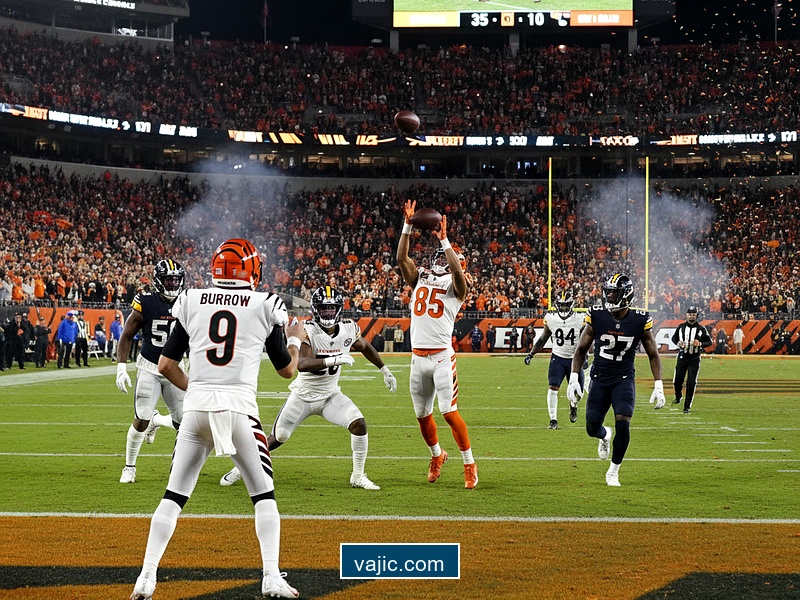

The Red Zone: Leverage and Vertical Displacement

The Bengals.com report notes a "new, improved run game" seeing red in the end zone, but let’s strip away the cliché. What actually changed? The Bengals have stopped trying to finesse the goal line and started embracing vertical displacement. In the scouting world, we look for "hat-on-hat" movement. The recent shift suggests a move toward "Duo" and "Inside Zone" concepts that rely on double teams at the point of attack rather than lateral stretching.

This shift is critical not just for the running backs, but for Burrow’s play-action efficacy. When an offense establishes a power run identity inside the 20, linebackers are forced to "trigger" downhill. They bite on the run keys. In the clinic put on against Miami, you could see the linebackers freezing at the mesh point (where the QB meets the RB). That hesitation creates the windows Burrow exploits.

This is "constraint theory" football. The run game forces the defense to contract, and Burrow punishes that contraction with perimeter throws. It’s not just about "balance"; it’s about geometric conflict. By forcing the defense to defend the A-gaps (the space between center and guard), Burrow gets one-on-one matchups on the outside where his ball placement makes coverage irrelevant.

Decoding the "Zero" and the Empty Set

One tactical aspect that went largely unnoticed in the general game recaps was Burrow’s command of "Empty" formations (five receivers, no backs). In modern NFL defensive schemes, the "Simulated Pressure" is king—showing blitz and dropping into coverage, or showing coverage and bringing the house. When Burrow goes Empty, he isn't just spreading the field; he is declaring the math.

If the defense shows a "Cover 0" look (all-out blitz, no safety help), Burrow doesn't panic. He identifies the "hot" receiver immediately. His processing speed here is elite. We measure "time-to-throw" not just from snap to release, but from "decision to release." Burrow’s decision is often made pre-snap based on the safety rotation. Against Miami, there were snaps where he manipulated the high safety with his helmet stripe—looking left to freeze the defender before firing a laser to the right seam. This is PhD-level manipulation.

"I’m having fun playing football, this is why you do it." — Joe Burrow via NBC Sports

That quote reads like a throwaway line, but in the context of his body language, it is terrifying for defensive coordinators. A quarterback having "fun" amidst violent collisions implies a slowing down of the game’s processing speed. He is no longer surviving; he is orchestrating.

The Unseen Grind: Jalen Davis and the Nickel Anatomy

While the offense grabs the ink, the mention of Jalen Davis in the Bengals.com report warrants a scout’s eye deep dive. The Nickelback position (slot corner) is arguably the second hardest position to play in a modern defense behind Quarterback. You are essentially a linebacker in the run fit and a corner in pass coverage, operating in the immense space of the middle field.

Davis’s journey isn’t just a feel-good story; it’s a testament to "trigger speed." Undersized corners survive in this league through superior diagnosis. Watching tape on Davis, his "click-and-close" ability—the time it takes to diagnose a throw and drive on the ball—is rapid. In a league dominated by Shanahan-style offenses that abuse the middle of the field with crossers and slants, a Nickel who can navigate "traffic" (avoiding "rub" routes and blockers) is priceless. The Bengals' defensive versatility allows Burrow to play with leads, knowing the backend can disguise coverages just as well as he disguises intentions.

Historical Context: The Evolution of the "Point Guard" QB

We are witnessing the evolution of the position. In the 90s, you had the gunslingers (Favre). In the 2000s, the cerebral assassins (Manning/Brady). Burrow represents the hybrid: The "Point Guard." He possesses the athletic twitch to extend plays (the "Second Reaction" phase), but his primary weapon is distribution based on leverage readings.

The 45-21 scoreline against Miami wasn't a fluke of big plays; it was death by a thousand cuts. It was the result of a quarterback who understands that a 4-yard check-down on 1st and 10 is a winning play because it keeps the offense "on schedule." This discipline is rare. Young quarterbacks want the highlight reel; Burrow wants the first down.

The Verdict

The "Third Quarter Struggles" mentioned in the Dolphins reports are a red herring. Adjustments take time. What matters is the counter-punch. The Bengals offense has evolved beyond simple execution; they are now in the phase of anticipation. Burrow isn't reacting to the defense; he is dictating the terms of engagement.

When you combine a run game that now demands respect in the A-gaps with a quarterback who manipulates pocket leverage with the subtlety of a grandmaster, you don't just get a win. You get a blueprint. The rest of the AFC North isn't looking at the 45 points with fear; they're looking at the tape of Burrow’s feet, and realizing that the window to rattle him has firmly shouted shut.